Nature as Oracle: Sigurd Olson’s Never-Ending Search for Spirituality in Wilderness

By Charles Dayton

Sigurd Olson: the very name conjures up visions-the North Woods, the deafening silence of the deep winter, campfire light flickering on a leathery face, the long low wail of the loon at sunset, a lone canoe slipping silently through the mist. His lyrical word pictures of the beauty of the North Country expressed the feelings of those fortunate enough to have been there and made it live for others who had not. But Sigurd Olson went far beyond nature’s beauty, in order to seek its meaning for the human spirit, and therein lies

\

\

his greatness. Sig’s experiences as a guide, a naturalist and a teacher had filled him with a great love that demanded release and expression. He described the process this way: “As time went on there was a certain fullness within me, more than mere pleasure or memory, a sort of welling up of powerful emotions that somehow must be used and directed. And so began a groping for a way of satisfying the urge to do something with what I had felt and seen, (something) that would give life and substance to thoughts and memories, a way of recapturing, and sharing again the experiences that were mine.”  He had a peak experience while viewing a simple and beautiful scene: “The little raft of ducks floating out in the open were caught that very instant in a single ray of light, and as the somber brown hills were brushed with it, the glow was around and within me.

He had a peak experience while viewing a simple and beautiful scene: “The little raft of ducks floating out in the open were caught that very instant in a single ray of light, and as the somber brown hills were brushed with it, the glow was around and within me.  “Then the sun dropped behind a cloud and the hills were dark as before, the ducks black spots against the water. But for a time, I saw them as they were in the glow, and knew nothing could ever be the same again.”

“Then the sun dropped behind a cloud and the hills were dark as before, the ducks black spots against the water. But for a time, I saw them as they were in the glow, and knew nothing could ever be the same again.” In that flash of insight he knew: he must write.

In that flash of insight he knew: he must write. “Suddenly the whole purpose of my roaming was clear to me, the miles of paddling and portaging, the years of listening, watching, and studying. I would capture it all, campsites and vistas down wild waterways, the crashing waves of storms and the roar of rapids,

“Suddenly the whole purpose of my roaming was clear to me, the miles of paddling and portaging, the years of listening, watching, and studying. I would capture it all, campsites and vistas down wild waterways, the crashing waves of storms and the roar of rapids, sparkling mornings to the calling of the loons sunsets and evenings, whitethroats and thrushes making music.Nights when the milky way was close enough to touch I would remember laughter and the good feeling after a long portage, and friendships on the trail.”

sparkling mornings to the calling of the loons sunsets and evenings, whitethroats and thrushes making music.Nights when the milky way was close enough to touch I would remember laughter and the good feeling after a long portage, and friendships on the trail.”  But, the editors of Sig’s earliest stories wanted only simple descriptions of adventure in the woods, and they slashed away “bits of philosophy or personal conviction.” Finally, the editors accepted an article with a philosophical tone, and encouraged him in his belief that the sense of awe and mystery that he felt for the wild, his belief that humans could sense the meaning of life from the timeless cycles of nature, should be expressed. In that article entitled “Search for the Wild,” Sig took issue with John Burroughs, a nature essayist. Burroughs had written that Thoreau viewed nature as an oracle questioning her as a naturalist and poet. While Sig agreed with Burroughs’ characterization, he disagreed strongly with Burroughs conclusion that Thoreau did not find what he was looking for. Convinced that the “lifetime search of Thoreau had been fruitful and what he sought and found in the woods and fields around Concord, Walden Pond, and the Merrimack River was what we all seek when we go into the bush, . . . I tried to prove that the never ending search for the essence of the wild was the underlying motive of all trips and expeditions…. I had dared speak of my deepest convictions, and for once there were no deletions. The first real encouragement I had ever had, it convinced me there was a field for this kind of writing.”

But, the editors of Sig’s earliest stories wanted only simple descriptions of adventure in the woods, and they slashed away “bits of philosophy or personal conviction.” Finally, the editors accepted an article with a philosophical tone, and encouraged him in his belief that the sense of awe and mystery that he felt for the wild, his belief that humans could sense the meaning of life from the timeless cycles of nature, should be expressed. In that article entitled “Search for the Wild,” Sig took issue with John Burroughs, a nature essayist. Burroughs had written that Thoreau viewed nature as an oracle questioning her as a naturalist and poet. While Sig agreed with Burroughs’ characterization, he disagreed strongly with Burroughs conclusion that Thoreau did not find what he was looking for. Convinced that the “lifetime search of Thoreau had been fruitful and what he sought and found in the woods and fields around Concord, Walden Pond, and the Merrimack River was what we all seek when we go into the bush, . . . I tried to prove that the never ending search for the essence of the wild was the underlying motive of all trips and expeditions…. I had dared speak of my deepest convictions, and for once there were no deletions. The first real encouragement I had ever had, it convinced me there was a field for this kind of writing.”  So, There it is: Sig believed that Thoreau was right that nature

So, There it is: Sig believed that Thoreau was right that nature

should be viewed as an oracle: nature speaking to humans of the wonders of the universe, nature as an intermediary between humankind and the divine. That is why he describes his peak experiences in the metaphors of sound, and urges us to “listen,” as he says, to “the singing wilderness,” “the Pipes of Pan,” “the music of the spheres.”  “I have listened to it on misty migration nights when the dark has been alive with the high calling of birds,

“I have listened to it on misty migration nights when the dark has been alive with the high calling of birds,  in rapids when the air was full of their rushing thunder,

in rapids when the air was full of their rushing thunder,  at dawn with the mists moving out of the bays, and on cold winter nights when the stars seemed close enough to touch.The music can be heard in the soft guttering of an open fire or in the beat of rain on a tent,

at dawn with the mists moving out of the bays, and on cold winter nights when the stars seemed close enough to touch.The music can be heard in the soft guttering of an open fire or in the beat of rain on a tent,

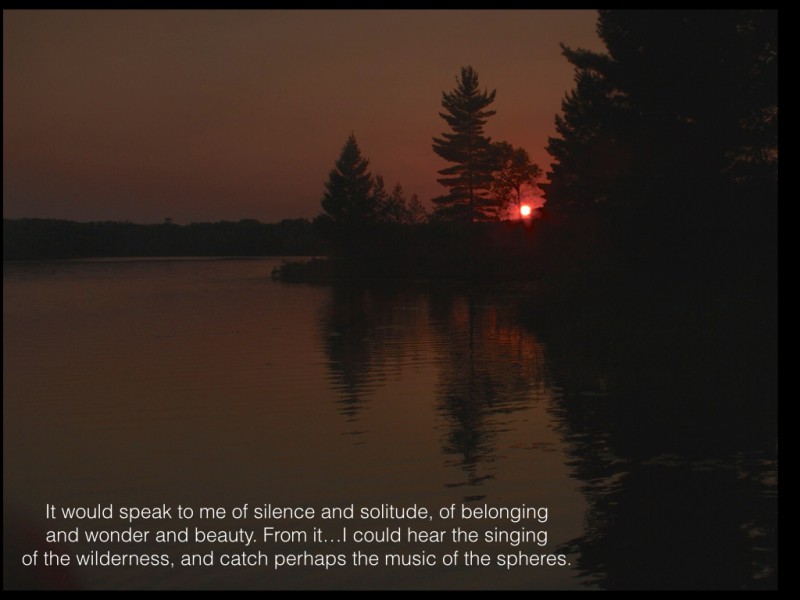

sometimes long afterward, like an echo out of the past, you know it is there in some quiet place, or while doing a simple task out of doors.  This is why he named his peninsula on Burntside Lake “Listening Point,” also the title of one of his best-loved books. He explained that, “only when one comes to listen, only when one is aware and still, can things be seen and heard. (This place) would speak to me of silence and solitude, of belonging and wonder and beauty. Though only a glaciated spit of rock on an island-dotted lake with twisted pines and caribou moss, I knew it would grow into my life and the lives of all who shared it with me. However small a part of the vastness reaching far to the Arctic, from it I could survey the whole, hear the singing of the wilderness, and catch perhaps the music of the spheres.”

This is why he named his peninsula on Burntside Lake “Listening Point,” also the title of one of his best-loved books. He explained that, “only when one comes to listen, only when one is aware and still, can things be seen and heard. (This place) would speak to me of silence and solitude, of belonging and wonder and beauty. Though only a glaciated spit of rock on an island-dotted lake with twisted pines and caribou moss, I knew it would grow into my life and the lives of all who shared it with me. However small a part of the vastness reaching far to the Arctic, from it I could survey the whole, hear the singing of the wilderness, and catch perhaps the music of the spheres.” What is this music of which Sig wrote? Perhaps, like a symphony, it cannot be captured completely on paper, but must be experienced to be understood. Notes on a page can tell us something of the music, and Sig’s words can convey beautifully his sense of the wholeness (and holiness) of all nature. But if we are to hear the singing, we must ourselves go out, be still, and listen. Sig intuitively understood the essence of Mary Oliver’s prescription for relating to nature: She said

What is this music of which Sig wrote? Perhaps, like a symphony, it cannot be captured completely on paper, but must be experienced to be understood. Notes on a page can tell us something of the music, and Sig’s words can convey beautifully his sense of the wholeness (and holiness) of all nature. But if we are to hear the singing, we must ourselves go out, be still, and listen. Sig intuitively understood the essence of Mary Oliver’s prescription for relating to nature: She said

Pay Attention,

Be Astonished,

Tell about it.

And what did Sig learn from a lifetime of such listening? Did he find the answer? Did he find God? He found that a sense of one’s place in the universe, and an understanding of the evolution of a human consciousness capable of knowledge and appreciation of beauty and mystery, is itself sufficient. He wrote: “For centuries, the searching has gone on for a God who is simple and understandable, one who can be incorporated into our lives naturally. How much better to feel the presence of godliness around and within us than to conjecture vainly as to exactly what form He should take. We shall never really know what God is, any more than the meaning of the Word.”

And what did Sig learn from a lifetime of such listening? Did he find the answer? Did he find God? He found that a sense of one’s place in the universe, and an understanding of the evolution of a human consciousness capable of knowledge and appreciation of beauty and mystery, is itself sufficient. He wrote: “For centuries, the searching has gone on for a God who is simple and understandable, one who can be incorporated into our lives naturally. How much better to feel the presence of godliness around and within us than to conjecture vainly as to exactly what form He should take. We shall never really know what God is, any more than the meaning of the Word.” “Man’s only goal is the evolution of his mind to the point where he becomes aware of love, beauty, and truth. This is the emergent God, and if man works toward it constantly in his outlook, thoughts, and actions, he may become Godlike.”

“Man’s only goal is the evolution of his mind to the point where he becomes aware of love, beauty, and truth. This is the emergent God, and if man works toward it constantly in his outlook, thoughts, and actions, he may become Godlike.”  “The great challenge is to build a base of knowledge and understanding of such depth, clarity, and power that it cannot be ignored. Only when we know what a balanced ecology really means can we live in harmony; only when we know intuitively that such values are more important than all others will we restore our flagging spirits.” “At last I am beginning to believe I am part of all this life and to know how I evolved from the primal dust to a creature capable of seeing beauty. This is compensation enough. No one can ever take this dream away; it will be with me until the day I have seen my last sunset and listened for a final time to the wind whispering through the pines.”

“The great challenge is to build a base of knowledge and understanding of such depth, clarity, and power that it cannot be ignored. Only when we know what a balanced ecology really means can we live in harmony; only when we know intuitively that such values are more important than all others will we restore our flagging spirits.” “At last I am beginning to believe I am part of all this life and to know how I evolved from the primal dust to a creature capable of seeing beauty. This is compensation enough. No one can ever take this dream away; it will be with me until the day I have seen my last sunset and listened for a final time to the wind whispering through the pines.”

As a guide, he knew the magical effect that a wilderness experience can have, particularly upon city folk burdened by schedules and deadlines.

He soon learned the importance of living by sunrise and sunset, and having the freedom to do what you feel like doing: “Men who hadn’t sung a note for years would suddenly burst into song. When one recalls the ages men lived as other creatures with no dependence on set routines, it is not surprising that once the pattern has been broken, men react strongly. No wonder when they return even for a short time to the ancient system to which they are really attuned, they know release.” This perspective drove Sig to his conviction that wilderness must be preserved for the human spirit.  “I sincerely believe if we can somehow retain places where we can always sense the mystery of the unknown, we will find strength and beauty. In this day of strife, floundering economies, threat of war and more war, we have need of the philosophy our forebears accepted.”

“I sincerely believe if we can somehow retain places where we can always sense the mystery of the unknown, we will find strength and beauty. In this day of strife, floundering economies, threat of war and more war, we have need of the philosophy our forebears accepted.”

When snowmobiles were first banned in the BWCA in 1975, a disgruntled snowmobiler derided the environmentalists’ efforts, complaining, “They think the Boundary Waters is the Holy Land.” For Sigurd Olson and many others, it is a sacred place, where foreign sounds are heresy. “Wilderness should be sacred and quiet, just as the Indians felt in designating certain places as spirit lands where no one talked. I have written about the Kawashaway River country of ‘no place between,’ where the Indians always traveled quietly and spoke only in whispers.”

“There is joy in finding new campsites, a place no one has camped before, where the rocks have not been moved since they were dropped by the great glacier ten thousand years before, rocks unscuffed by human feet and covered with lichens and mosses of many hues. In such a haven there are no scars or ax marks, no indications of use by others. To me they are holy and sacred and must not be disturbed, and I am careful to step softly around patches of caribou moss so as not to crunch the brittle growth with a careless step, for one has the feeling there of being part of the primeval.” “There were special places ,

“There is joy in finding new campsites, a place no one has camped before, where the rocks have not been moved since they were dropped by the great glacier ten thousand years before, rocks unscuffed by human feet and covered with lichens and mosses of many hues. In such a haven there are no scars or ax marks, no indications of use by others. To me they are holy and sacred and must not be disturbed, and I am careful to step softly around patches of caribou moss so as not to crunch the brittle growth with a careless step, for one has the feeling there of being part of the primeval.” “There were special places ,

of deep silence, one a camp on a small island above the Pictured Rocks on Crooked Lake, a rocky, glaciated point looking toward the north, a high cliff on one side balanced by a mass of dark timber on the other. Each night we sat there looking down the waterway, listening to the loons filling the darkening narrows with wild reverberating music. But

it was when they stopped that the quiet descended, an all-pervading stillness that absorbed all the sounds that had ever been. No one spoke. We sat there so removed from the rest of the world and with such a sense of complete remoteness that any sound would have been a sacrilege.” Sig’s sense of ecology, and the unity of all things, grew slowly but unerringly. In the early days, he saw the slash and burn logging, and the poisoning of wolves. He sensed the wrong, but made little fuss then. Gradually, as his formal scientific training combined with his deepening sense of the importance of wilderness, every fiber of his being became imbued with the belief that nothing is more important than wilderness preservation.

Sig’s sense of ecology, and the unity of all things, grew slowly but unerringly. In the early days, he saw the slash and burn logging, and the poisoning of wolves. He sensed the wrong, but made little fuss then. Gradually, as his formal scientific training combined with his deepening sense of the importance of wilderness, every fiber of his being became imbued with the belief that nothing is more important than wilderness preservation.  He got it, and he got it deeply. He wrote: “One summer I had the good fortune to spend several months with a scientific expedition studying the Quetico-Superior and its various creatures in relation to their habitat.

He got it, and he got it deeply. He wrote: “One summer I had the good fortune to spend several months with a scientific expedition studying the Quetico-Superior and its various creatures in relation to their habitat.  It was then I first caught the meaning of ecology as a concept, and as I look back, one thing stands out, its impact as a basic understanding. More than knowledge, it was deeply involved with my own attitude and emotional reaction to the wilderness.

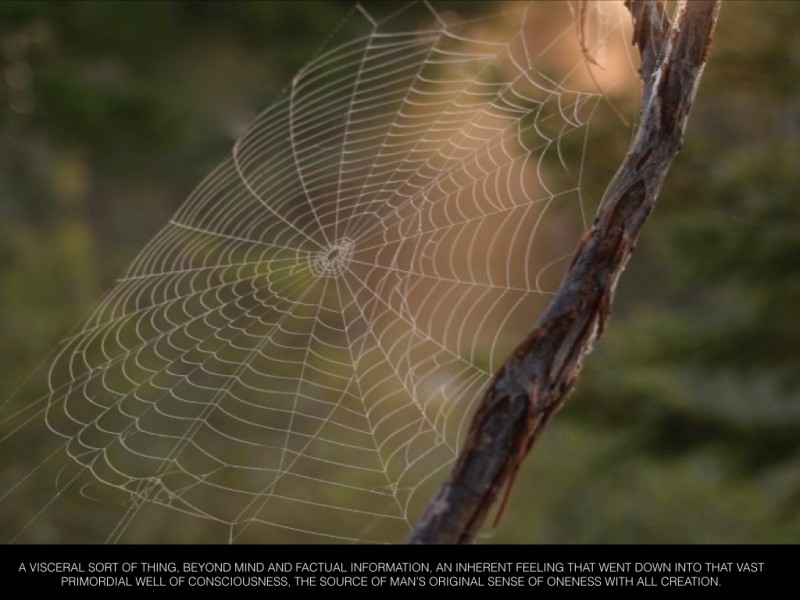

It was then I first caught the meaning of ecology as a concept, and as I look back, one thing stands out, its impact as a basic understanding. More than knowledge, it was deeply involved with my own attitude and emotional reaction to the wilderness.  “A visceral sort of thing beyond mind and factual information, it was an inherent feeling that went down into that vast primordial well of consciousness, the source of man’s original sense of oneness with all creation, a perspective reinforced with logic and reason, cause and effect, and scientific method.”

“A visceral sort of thing beyond mind and factual information, it was an inherent feeling that went down into that vast primordial well of consciousness, the source of man’s original sense of oneness with all creation, a perspective reinforced with logic and reason, cause and effect, and scientific method.”  And isn’t this true of a lot of us? Maybe we can’t express it as eloquently as Sig, but many in this room have that gut feeling about the wilderness. It is a part of our being, beyond words, real but inexpressible, like the memory of the first time we were in love or the thrill of holding a grandchild. Tens of thousands of comments on the EIS for the new Polymet sulfide mining operation bear witness to that deep love, as do the heroic efforts that many are making now to combat the threat of Sulfide mining.

And isn’t this true of a lot of us? Maybe we can’t express it as eloquently as Sig, but many in this room have that gut feeling about the wilderness. It is a part of our being, beyond words, real but inexpressible, like the memory of the first time we were in love or the thrill of holding a grandchild. Tens of thousands of comments on the EIS for the new Polymet sulfide mining operation bear witness to that deep love, as do the heroic efforts that many are making now to combat the threat of Sulfide mining.  And so Sig led the great battles to preserve the great remaining wilderness of northern Minnesota and southern Ontario, the Quetico-Superior. Born in 1899, his birthdays nearly coincided with the numerical years of the century, and the history of the struggles for the northern wilderness is the story of much of his life. In the early twenties, and his early twenties, a great road-building program was promoted in the name of resort development. No sooner had that scheme been squelched in 1926 than a huge dam project that would have flooded the entire border country for power reservoirs, was promoted and finally stopped in 1934. Shortly after that battle, Sig wrote of a night that he spent at Curtain Falls, which would have been flooded by the dam project

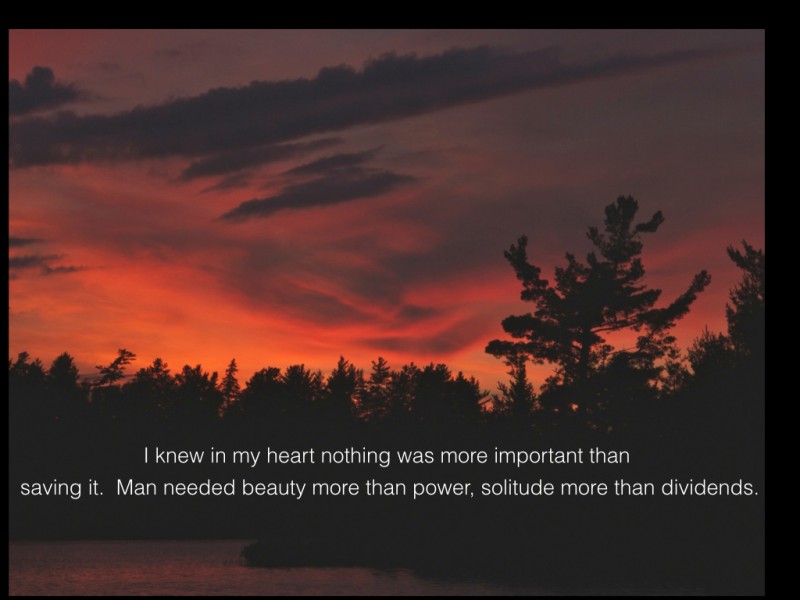

And so Sig led the great battles to preserve the great remaining wilderness of northern Minnesota and southern Ontario, the Quetico-Superior. Born in 1899, his birthdays nearly coincided with the numerical years of the century, and the history of the struggles for the northern wilderness is the story of much of his life. In the early twenties, and his early twenties, a great road-building program was promoted in the name of resort development. No sooner had that scheme been squelched in 1926 than a huge dam project that would have flooded the entire border country for power reservoirs, was promoted and finally stopped in 1934. Shortly after that battle, Sig wrote of a night that he spent at Curtain Falls, which would have been flooded by the dam project  The islands lay like black silhouettes against the glow of sunset, the dusk was alive with the calling of loons. That night it seemed incredible that anyone would want to transform such a scene into kilowatts and profit and I knew in my heart nothing was more important than saving it. Man needed beauty more than power, solitude more than dividends.”

The islands lay like black silhouettes against the glow of sunset, the dusk was alive with the calling of loons. That night it seemed incredible that anyone would want to transform such a scene into kilowatts and profit and I knew in my heart nothing was more important than saving it. Man needed beauty more than power, solitude more than dividends.”  In the forties, Ely became the largest inland seaplane base on the continent, and resorts sprang up in the interior, even at Curtain Falls. Sig and others would paddle and portage for days, seeking to escape the float planes, only to find the silence shattered by another engine. Finally, after the war ended, President Truman signed the executive order banning airplanes in 1948. Later, in the 1950s, many of the resorts in the roadless areas were closed down under the Thye-Blatnik Act. The Wilderness Act of 1964 passed exactly 50 years ago, took seven years of debate and controversy, and Sig was a key part of all that.

In the forties, Ely became the largest inland seaplane base on the continent, and resorts sprang up in the interior, even at Curtain Falls. Sig and others would paddle and portage for days, seeking to escape the float planes, only to find the silence shattered by another engine. Finally, after the war ended, President Truman signed the executive order banning airplanes in 1948. Later, in the 1950s, many of the resorts in the roadless areas were closed down under the Thye-Blatnik Act. The Wilderness Act of 1964 passed exactly 50 years ago, took seven years of debate and controversy, and Sig was a key part of all that.  He continued to be involved in the ongoing battles throughout the decade of the seventies, in his seventies. In 1972, he was a witness in MPIRG’s lawsuit to stop logging in the BWCA, and that’s when I got to know him. Footnote: My grandson, Jason Dayton, is now on the board of MPIRG . By the summer of 1974, the Forest Service had completed an environmental impact statement concerning logging, as required by Judge Miles Lord, but announced its decision to continue logging the BWCA nevertheless. Environmentalists realized that the time had come to ask Congress to amend the Wilderness Act to ban logging in this last large stand of virgin timber in the eastern half of the country. A national BWCA strategy session was held in Ely, and the “Green Mafia” was there including Washington lobbyists for the Sierra Club and the Wilderness Society and representatives of all the major groups. About 25 of us disciples sat on the floor of the Old log cabin at Listening Point, at the feet of the wise master. As he did many times, Sig stressed that if any of the battles to preserve wilderness had been lost, we simply .

He continued to be involved in the ongoing battles throughout the decade of the seventies, in his seventies. In 1972, he was a witness in MPIRG’s lawsuit to stop logging in the BWCA, and that’s when I got to know him. Footnote: My grandson, Jason Dayton, is now on the board of MPIRG . By the summer of 1974, the Forest Service had completed an environmental impact statement concerning logging, as required by Judge Miles Lord, but announced its decision to continue logging the BWCA nevertheless. Environmentalists realized that the time had come to ask Congress to amend the Wilderness Act to ban logging in this last large stand of virgin timber in the eastern half of the country. A national BWCA strategy session was held in Ely, and the “Green Mafia” was there including Washington lobbyists for the Sierra Club and the Wilderness Society and representatives of all the major groups. About 25 of us disciples sat on the floor of the Old log cabin at Listening Point, at the feet of the wise master. As he did many times, Sig stressed that if any of the battles to preserve wilderness had been lost, we simply .

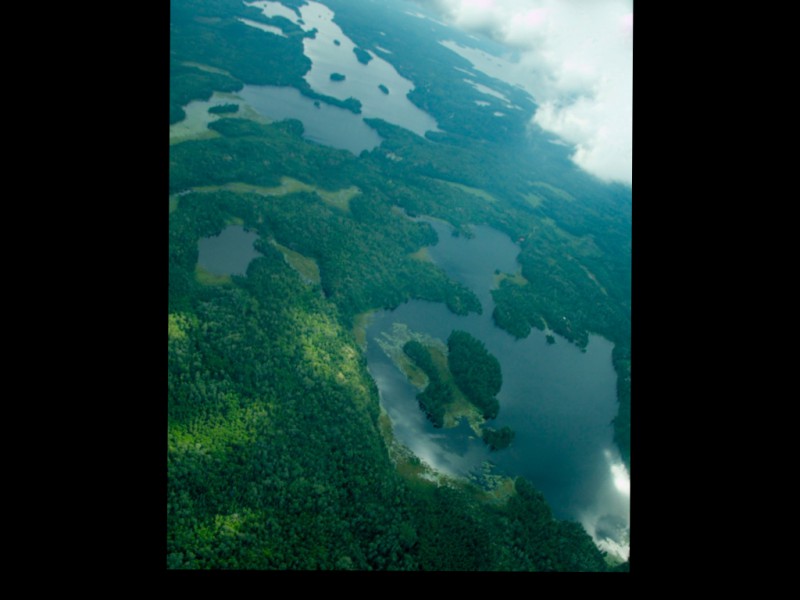

would no longer have itHe said, “I have traveled all over this continent, but this Quetico-Superior country, with its countless glaciated lakes and interconnecting waterways is a gem, it’s the best there is, there is no place on earth like it. It simply must be preserved.” Sigurd Olson knew that only people who truly love the land are willing to fight for it, and that his sharing of that love helped to give others the will and commitment to become activists. Such emotional commitment and love helped him to ignore the shouts and jeers of his lifelong Ely neighbors, who hung him in effigy at the 1977 Congressional hearing in Ely.  That same year, he wrote prophetically that love for the earth “gives environmentalists the strength to battle for the land they love, to take scorn and epithets in their stride, knowing they are fighting for something eternal; if they win, the world will be a more beautiful place in which to live. They have dedication and resolve, an inherent vision that will not accept defeat.”

That same year, he wrote prophetically that love for the earth “gives environmentalists the strength to battle for the land they love, to take scorn and epithets in their stride, knowing they are fighting for something eternal; if they win, the world will be a more beautiful place in which to live. They have dedication and resolve, an inherent vision that will not accept defeat.”  Sig died with his snowshoes on, and whether or not he had any notion that the end was near, his writings leave no doubt that it was a way of going that he would have approved. He wrote about a friend, who died running a rapids, that he “went the way he wanted to go, with the sound of white water in his ears.” Similarly, he wrote of an old timer he had known in Wisconsin who had wanted to die with his boots on listening to the rapids and the whitethroats: “After his passing I thought of Kahlil Gibran where he says, ‘For life and death are one even as the river and sea are one and what is it to die but to stand naked in the wind and to melt into the sun and drink from the river of silence.’ ” Sig believed that immortality is found in memories of those we cannot forget. “Certainly they are gone physically and ‘dust to dust’ is no empty phrase, but the real truth in what they were and did lives on, each person leaving his own evidence of his time on earth. It is like a stone thrown into a calm pool, its ripples spreading wider and wider, possibly into infinity.” Such immortality is already his, and the banner he carried will be borne by present and future generations, in large measure because Sigurd Olson had the spirit, the will, the ability, and the discipline to give expression to his bursting love for the wild.

Sig died with his snowshoes on, and whether or not he had any notion that the end was near, his writings leave no doubt that it was a way of going that he would have approved. He wrote about a friend, who died running a rapids, that he “went the way he wanted to go, with the sound of white water in his ears.” Similarly, he wrote of an old timer he had known in Wisconsin who had wanted to die with his boots on listening to the rapids and the whitethroats: “After his passing I thought of Kahlil Gibran where he says, ‘For life and death are one even as the river and sea are one and what is it to die but to stand naked in the wind and to melt into the sun and drink from the river of silence.’ ” Sig believed that immortality is found in memories of those we cannot forget. “Certainly they are gone physically and ‘dust to dust’ is no empty phrase, but the real truth in what they were and did lives on, each person leaving his own evidence of his time on earth. It is like a stone thrown into a calm pool, its ripples spreading wider and wider, possibly into infinity.” Such immortality is already his, and the banner he carried will be borne by present and future generations, in large measure because Sigurd Olson had the spirit, the will, the ability, and the discipline to give expression to his bursting love for the wild.  For many who knew him, or who have read his works, Sig’s influence will be most intense sitting silently by a lake, perhaps in the last level rays of the sun, listening for the haunting music of which he wrote. May the wilderness sing to us and to our children and grandchildren as it did to him “of silence and solitude, of belonging and wonder and beauty,” and may we honor his legacy by introducing children to a life-long love of the wild.

For many who knew him, or who have read his works, Sig’s influence will be most intense sitting silently by a lake, perhaps in the last level rays of the sun, listening for the haunting music of which he wrote. May the wilderness sing to us and to our children and grandchildren as it did to him “of silence and solitude, of belonging and wonder and beauty,” and may we honor his legacy by introducing children to a life-long love of the wild.

(Note: The quotations are from “Open Horizons,” “Reflections from the North Country,” and “Wilderness Days.” This is a talk, illustrated by my photos, that I gave to the Listening Point Foundation on April 26, 2014. The materials were originally collected for an article for Northland College at the time of Sig’s death in 1982, and Senator Dave Durenburger posted it in the Congressional record.)